Science, Desire – and Bodies – in 19th Century Edinburgh

“To hear my mother tell the story, my decision to abandon my studies at Oxford was enough to disgrace my father into an early grave. Regardless of his habits – his drinking, his gambling, his debts – in her mind, it was my own act of reckless rebellion that finally put him under.

“To that end, it’s perhaps for the best that he wasn’t alive six months later, when I was nearly arrested for smuggling a naked corpse in a wheelbarrow down Chambers Street at half past midnight.”

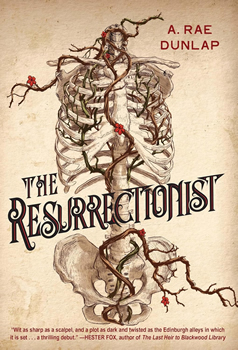

Edinburgh, 1828. In A. Rae Dunlap’s The Resurrectionist, James Willoughby, the third son of a family with a title, but little money, has rejected his parents’ plans that he become a cleric, and instead headed to Scotland to study medicine.

And, indeed, he has a lot to learn. The university lectures are good, he is told, but he will never learn anything about the human body unless he also goes to a private surgical school, where the cadavers are fresh and the experience is hands-on.

But where do the cadavers come from? Ah, well…and that is how James is introduced to the Resurrectionists, the men who snatch newly-interred bodies from the graveyards and bring them to the schools. It is a noble mission, they say. Without those bodies, no one would ever learn the secrets “of man himself, of sinew and bone and humour and blood….Our motivation is not the value of the bodies we steal, but in the second life we give them; postmortem Prometheus, bringing fire to mankind.”

James is convinced. It doesn’t hurt, either, that the leader of his crew is Aneurin “Nye” MacKinnon, dashing, talented, whip-smart, with pale, bottomless gray eyes. Yes, James has finally found his place in the world.

Until that world changes around him. Rival gangs come in from London, well-financed and ruthless. Bodies start turning up that are a little too fresh. A pair of men named Burke and Hare seem to have access to a surprisingly large supply. And his family, having caught him with Nye, commands him to an arranged marriage, or he will not like the consequences. And James knows all too well what those consequences are.

Vivid, twisty, rollicking, sometimes macabre, always entertaining. The Resurrectionist is a memorable exploration of the twin poles of science and desire – and the lengths to which we will go for both.

Says the author, “I learned about the body snatchers of Edinburgh while engaging in my favorite touristy pastime: Taking a ghost tour! One of our stops was the Greyfriars Kirkyard Cemetery, a fascinating site filled with relics from the age of snatching: Mortsafes, vaults, and table tombstones abound. I was so enthralled by the morbid history of this real-life cemetery that I made it a central location in my novel.

“By pure coincidence, a few weeks after my visit to Edinburgh, I listened to an episode of Aaron Mahnke’s podcast Lore, which detailed the crime spree of Burke and Hare. I was drawn in by the sensational murders, of course, but also by the macabre genius of the body snatchers and their unique methodologies.

“I was initially tempted to simply write a work of historical fiction centered around a body snatcher and his crew, but the story of Burke and Hare kept drawing me back. It was such a perfect microcosm of the colliding ideals of the era: the excitement of the New Enlightenment and the scientific progress that it brought, completely at odds with the religious and ethical norms that dominated the legal framework and social mores of the time. There was simply no better parable to highlight the consequence of these unresolved tensions”

Her influences were many:

“True crime historian Kate Winkler-Dawson did an incredible job of humanizing the victims of real-life serial killers Burke and Hare in her podcast, Tenfold More Wicked, and it’s truly a credit to her research that I felt inspired to include many of these individuals in this novel. Some of the more minor characters based on real people, such as Ferguson and the Grays, are there as nods to the true crime fanatics who know about Burke and Hare already and would appreciate the dramatic irony of seeing familiar names pop up amidst a fictionalized narrative. Lastly, my outrage over the deferred culpability of William Hare and Dr. Knox is evident in how the book concludes; There was no true justice in this case, in my opinion, and that fact will haunt me for a long time.

“I’ve also been interested in medical research and history for a long time, and this book gave me just the excuse I was looking for to delve into the topic. Most of my research was done online, reading through archived copies of old medical journals and first-hand student testimonials.

“One of my primary literary influences for this book was (perhaps surprisingly) Jane Austen; though she wrote about the Regency Era from a female perspective, her depiction of daily life, societal pressures, and her characters’ personal growth was a touchstone on which I firmly relied when bringing James’s character to life.

“But the biggest influence in my writing career has undoubtedly been my mother. She was a seventh-grade English teacher for over thirty years and shared with me her love of literature and learning. Even though I never had her as a teacher, throughout my time in grade school she made me do the same assignment she gave all her students. Writing two full five-sentence paragraphs every weekend, no matter what. I used to resent her for it, but now I have to credit her for instilling in me the work ethic and willingness to just write (even if it’s bad!). Writing something is always better than nothing, and perfection is the enemy of progress. I’ll carry those lessons with me for the rest of my life.”

There are many tonal shifts in the book – suspense, adventure, mystery, dark humor, heartfelt romance, even horror. How hard was it to pull of that tricky balance?

“I initially really struggled with this when I was writing. I felt like every element – from the dark humor to the romance to the horror – was integral to James’s story, yet it was challenging to define what it all meant as a cohesive piece. As one of my friends described it: it’s a ‘thriller coming-of-age story.’ And the coming-of-age process has a little bit of everything, just like the novel! James is figuring out who he wants to be as a son, a brother, an aristocrat, a doctor, a friend, a partner – all while combating sinister forces surrounding him. That journey is fraught with a wild combination of emotions and experiences for all of us, and James is no exception.”

Among those emotions and experiences is his newfound love affair with Nye, which, of course, adds extra jeopardy. Queer crime fiction has been around for a long time, but just in the last few years, there’ve been several excellent novels looking specifically at historical crime fiction through a queer lens – books set in 1950s Los Angeles; 1950s Washington, D.C.; an English country house in 1899; the dockyards of Tacoma, Washington, in 1888; Paris in 1884; and now 1828 Edinburgh. Why does she think we’re seeing this now?

“This is a complex question, and the answer is undoubtedly much more nuanced that we can capture in a single interview!

“That said, queerness has always existed throughout history, but only somewhat recently can these stories be told without dire personal risk – not just of ostracization, but imprisonment or death, as was the case in the period in which my novel is set. By telling these stories now, modern readers of all identities are reminded that queer individuals lived, loved, thrived – and solved crimes! – as valuable members of society, even when their private lives were fated to secrecy for their own safety.”

Next up: “Another true crime/historical fiction mashup.” At least the process will be easier this time than it initially was for The Resurrectionist:

“I was incredibly lucky to have my talented friend Caroline Frost (author of the brilliant Shadows of Pecan Hollow and The Last Verse) publish her first novel at around the time I finished the manuscript. I knew nothing about the publishing industry, and having just navigated it for the first time herself, she was an invaluable resource in helping me figure out the next steps.

“I initially went with a different agent who had been the first to make an offer to represent the manuscript. Then… nothing. Months of waiting and radio silence turned into endless frustration.

“Then one day, out of the blue, Laura Bradford emailed me to inquire about the status of the book. Although I had decided to go with a different agent, she told me this was one that she couldn’t quite let go.

“The fact that she was still thinking about my book all those months later was all it took to let me know Laura was the right person for the job. She scooped it up and sold it head-spinningly fast—a true pro! I’m forever grateful.”

Once you pick up The Resurrectionist, you’ll be grateful, too.

Neil Nyren is the former EVP, associate publisher, and editor in chief of G.P. Putnam’s Sons and the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among the writers of crime and suspense he has edited are Tom Clancy, Clive Cussler, John Sandford, C. J. Box, Robert Crais, Carl Hiaasen, Daniel Silva, Jack Higgins, Frederick Forsyth, Ken Follett, Jonathan Kellerman, Ed McBain, and Ace Atkins. He now writes about crime fiction and publishing for CrimeReads, BookTrib, The Big Thrill, and The Third Degree, among others, and is a contributing writer to the Anthony/Agatha/Macavity-winning How to Write a Mystery.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet.

- Backlash by Ian Coates - December 11, 2024

- What the Wife Knew by Darby Kane - December 11, 2024

- Booktrib Spotlight: A. Rae Dunlap - December 6, 2024